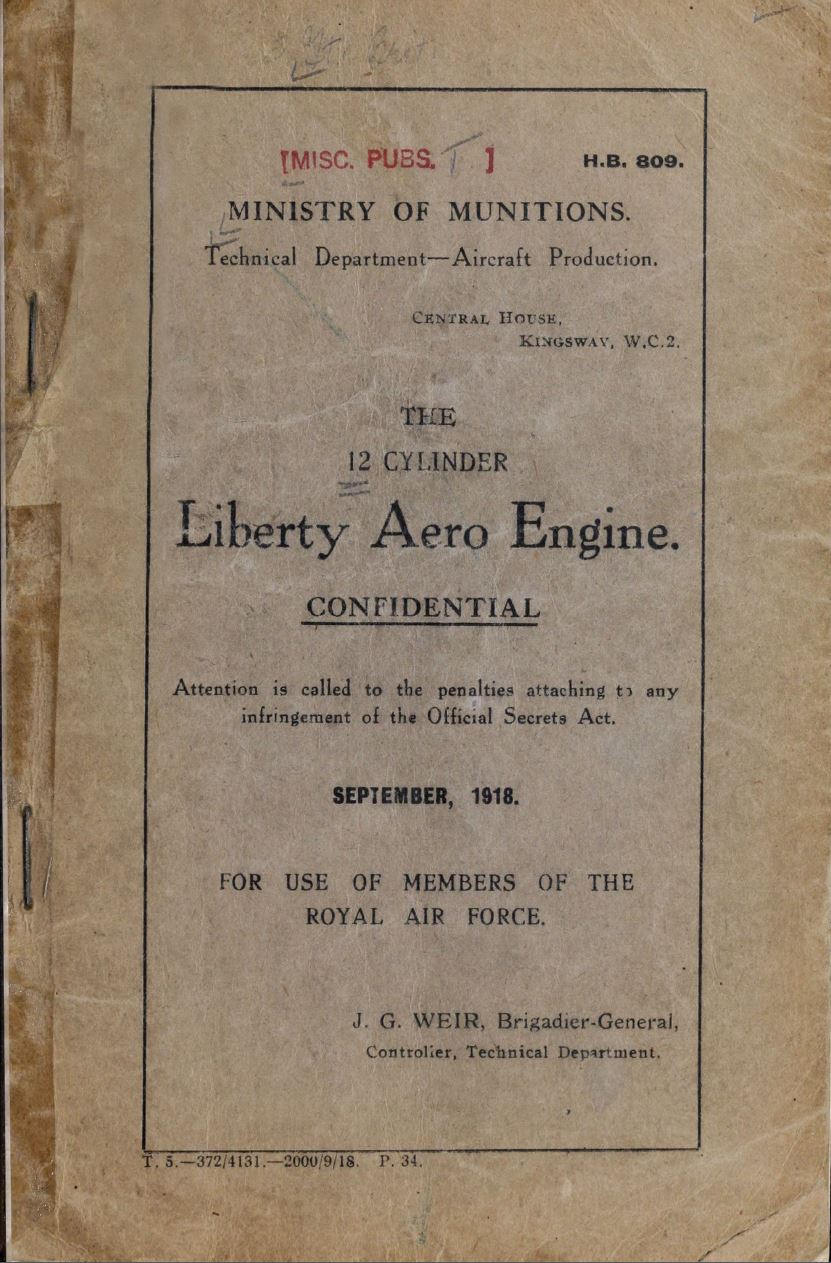

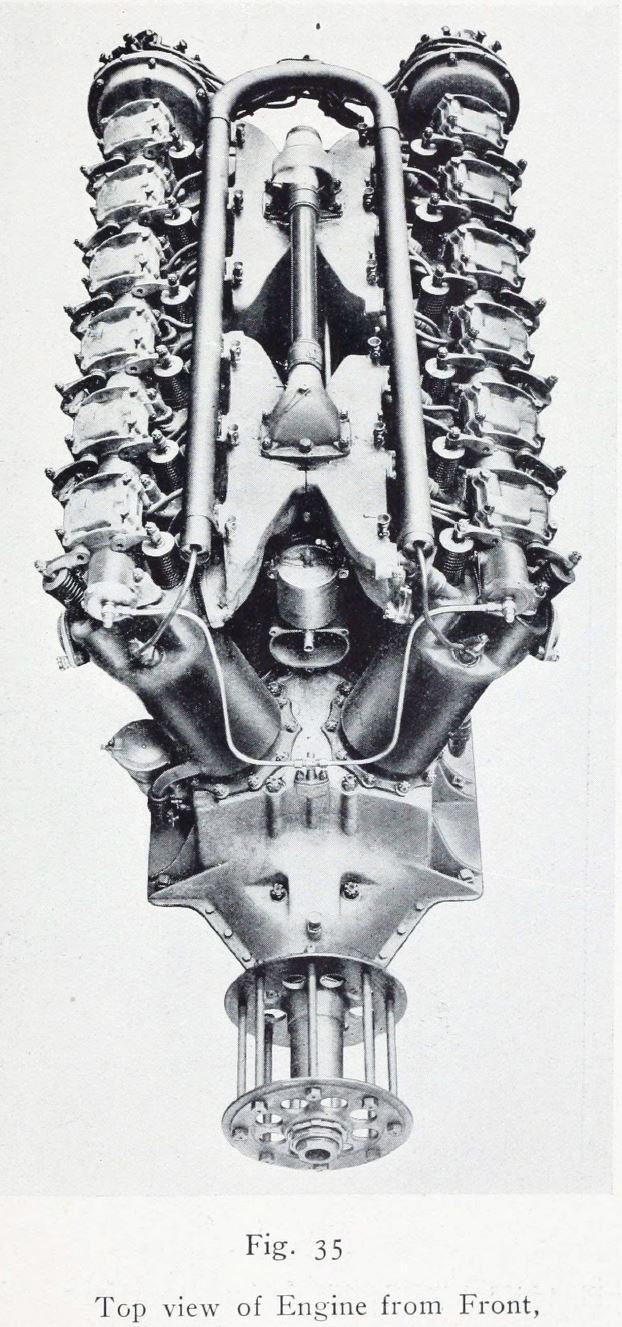

The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. The Aircraft Production Board, then headed up by Howard E. Coffin of the Hudson Motor Car Co. and his assistant Edward A. Deeds, a major stockholder in Delco, set the basic parameters for what would come to be known as the Liberty. The new engine would be lighter and slightly more powerful than the Rolls-Royce Eagle. Modular construction, employing common cylinder and valve components, would slash development time and permit the engine to be used on all types of airplanes from trainers to heavy bombers. And all this would be accomplished within the strictures of a conservative design philosophy.

The first of many expedients was to telescope layout into a two-day (some say five-day) marathon at the New Willard hotel in Washington, DC that begun in the afternoon of May 31, 1917. At General Pershing's request, the L-8 was put on hold in favor of a 12-cylinder L-12 that would be more powerful than existing Allied engines. The first of these was tested in August, 1918.

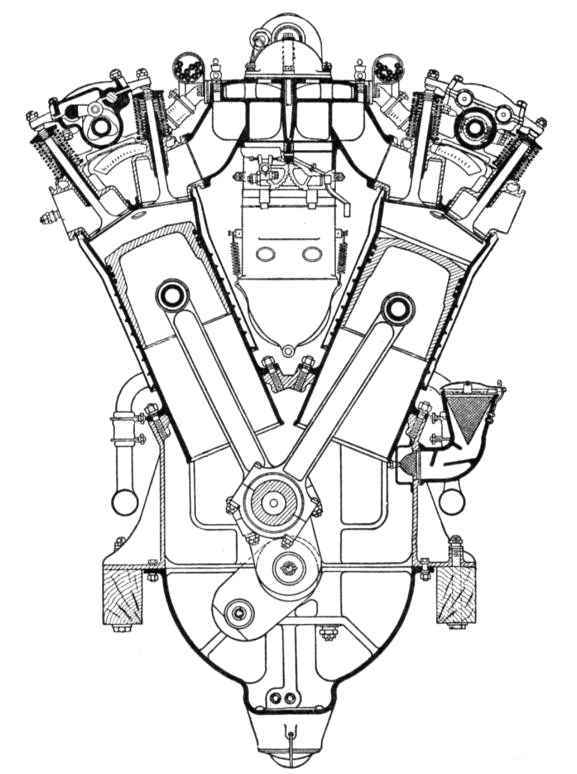

The 45º cylinder angle raised questions about torsional vibration. Robert J. Raymond demonstrated that the L-12 crankshaft underwent severe torque peaks at 1,333 rpm, 1,714 rpm and 2,000 rpm. Any of these inputs could result in failure. Raymond quotes two studies dating from the 1930s that indicate the presence of torsional vibration at certain operating speeds. One of these studies described Liberty crankshaft breakage as "epidemic."

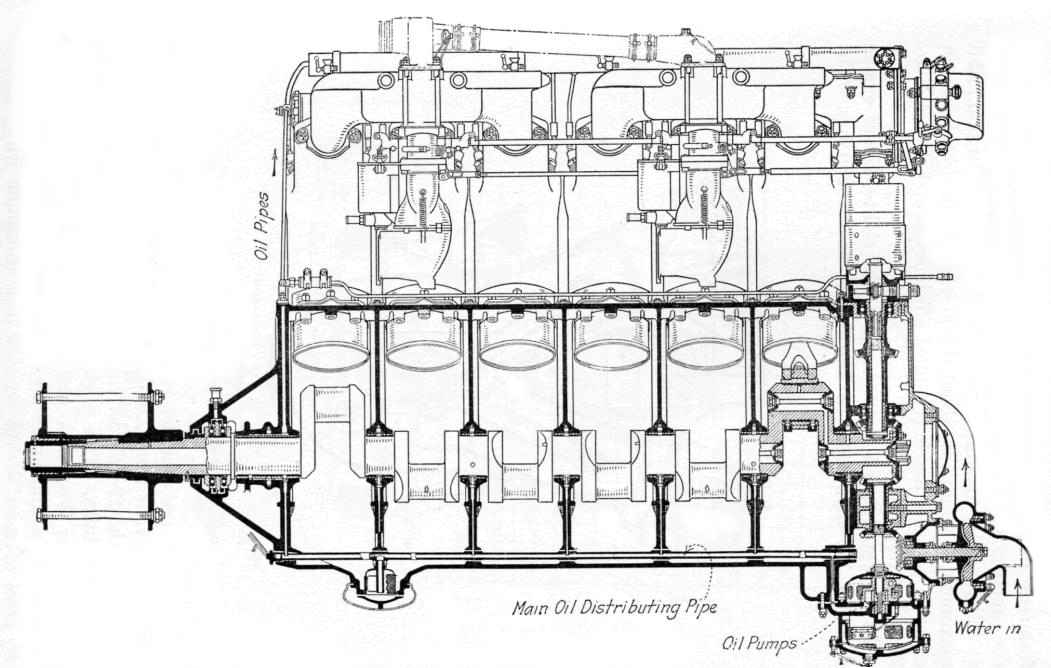

The Liberty had other faults. C. Fayette Taylor, who was in a position to know, reported that half of the early production engines could not pass the 50-hr acceptance test. Burnt exhaust valves and, as has been pointed out, accessory-gear failures were common on all versions.

TBO, or time between overhauls, is the primary measure of durability. By 1926 Navy L-12s were averaging 75 hours between overhauls. Newer air-cooled engines had TBOs of 300 hours

Once the war ended, the problem became what to do with the engines, for which few airframes were available. Some were donated to the Air Mail Service and vocational schools, and others were sold as surplus for pennies on the dollar. Rum runners found that 400 hp gave them an advantage over Coast Guard cutters. Still, by 1924, 11,810 L-12s remained in inventory, enough to satisfy military needs for 26 years.

Although the Liberty had very limited application for military aircraft, the overhang made it difficult to justify acquisition of newer and more expensive power plants.

Attempts to convince commercial operators to adopt the engine on economic grounds failed. It vibrated, weighed more than it should, and had a reputation for unreliability. Army mechanics did their part by foregoing overhauls. When an L-12 needed work, they replaced it with a new one. That practice continued until 1929.

Used on the 1924 Douglas World Cruiser

enginehistory.org Notes on the Liberty Aircraft Engine

(Wikipedia) -

Liberty L-12