Wikipedia - Distant Early Warning Line

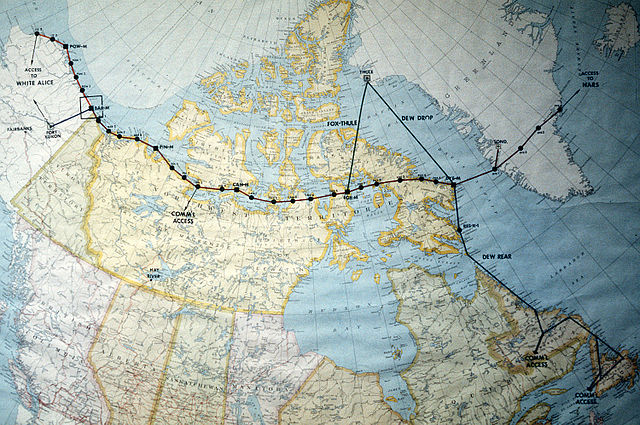

The Distant Early Warning Line, also known as the DEW Line or Early Warning Line, was a system of radar stations in the far northern Arctic region of Canada, with additional stations along the North Coast and Aleutian Islands of Alaska (see Project Stretchout and Project Bluegrass), in addition to the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Iceland. It was set up to detect incoming Soviet bombers during the Cold War, and provide early warning of any sea-and-land invasion.

The DEW Line was the northernmost and most capable of three radar lines in Canada and Alaska. The first of these was the joint Canadian-US Pinetree Line, which ran from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island just north of the Canadian border, but even while it was being built there were concerns that it would not provide enough warning time to launch an effective counterattack. The Mid-Canada Line (MCL) was proposed as an inexpensive solution using a new type of radar. This provided a "trip wire" warning located roughly at the 55th parallel, giving commanders ample warning time, but little information on the targets or their exact location. The MCL proved largely useless in practice, as the radar return of flocks of birds overwhelmed signals from aircraft.

The DEW Line was proposed as a solution to both of these problems, using conventional radar systems that could both detect and characterize an attack, while being located far to the north where they would offer hours of advanced warning. This would not only provide ample time for the defenses to prepare, but also allow the Strategic Air Command to get its active aircraft airborne long before Soviet bombers could reach their bases. The need was considered critical and the construction was given the highest national priorities. Advanced site preparation began in December 1954, and the construction was carried out in a massive logistical operation that took place mostly during the summer months when the sites could be reached by ships. The 63-base Line reached operational status in 1957. The MCL was shut down in the early 1960s, and much of the Pinetree line was given over to civilian use.

In 1985, as part of the "Shamrock Summit", the US and Canada agreed to transition DEW to a new system known as the North Warning System (NWS). Beginning in 1988, most of the original DEW stations were deactivated, while a small number were upgraded with all-new equipment.[1] The official handover from DEW to NWS took place on 15 July 1993.

Introduction

The shortest (great circle) route for a Russian air attack on North America is through the Arctic, across the North Pole. The DEW Line was built during the Cold War to give early warning of a Soviet nuclear strike, to allow time for US bombers to get off the ground and land-based ICBMs to be launched, to reduce the chances that a preemptive strike could destroy US strategic nuclear forces. The original DEW line was designed to detect bombers and was unable to detect intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). To give warning of this threat, in 1958 a more sophisticated radar system was constructed, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS).

The DEW Line was a significant achievement among Cold War initiatives in the Arctic. A successful combination of scientific design and logistical planning of the late 1950s, the DEW Line consisted of a string of continental defence radar installations, ultimately stretching from Alaska to Greenland. In addition to the secondary Mid-Canada Line and the tertiary Pinetree Line, the DEW Line marked the edge of an electronic grid controlled by the new SAGE (Semi Automatic Ground Environment) computer system and was ultimately centered at the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, Colorado, command hub of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).

The construction of the DEW Line was made possible by a bilateral agreement between the Canadian and US governments, and by collaboration between the US Department of Defense and the Bell System of communication companies. The DEW Line grew out of a detailed study made by a group of the nation's foremost scientists in 1952, the Summer Study Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The subject of the study was the vulnerability of the US and Canada to aerial bombing attacks, and its concluding recommendation was that a distant early warning line of search radar stations be built across the Arctic border of the North American continent as rapidly as possible.

Development and construction

Improvements in Soviet technology rendered the Pinetree Line and Mid-Canada Line inadequate to provide enough early warning and on 15 February 1954, the Canadian and American governments agreed to jointly build a third line of radar stations (Distant Early Warning), this time running across the high Arctic. The line would run roughly along the 69th parallel north, about 200 miles or 300 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle.

Before this project was completed, men and women with the necessary knowledge, skills, and experience were drawn from Bell Telephone companies in every state in the US, and many Canadian provinces. Much of the responsibility was delegated under close supervision to a vast number of subcontractors, suppliers, and US military units.

The initial contract with the U.S. Air Force and the Royal Canadian Air Force provided for the design and construction of a small experimental system to determine at the beginning whether the idea was practicable. The designs of communication and radar detection equipment available at the time were known to be unsuited to the weather and atmospheric conditions to be encountered in the Arctic. Prototypes of several stations were designed and built in Alaska in 1953. A prototype built for training purposes was chosen to be located in Streator, Illinois in 1952. The Streator DEW-Line Training Center became operational in 1956 and closed when operations were moved to Colorado Springs in 1975. After leaving Streator, the land on which the Streator DEW-Line Training Center stood was sold back to a farmer, who happened to be the descendant of the farmer who originally sold the land to the United States government. While few of the original designs for either buildings or equipment were retained, the trial installations did prove that the DEW Line was feasible, and they furnished a background of information that led to the final improved designs of all facilities and final plans for manpower, transportation, and supply.

With the experimental phase completed successfully, the Air Forces asked the Western Electric Company to proceed as rapidly as possible with the construction of the entire DEW Line. That was in December 1954, before the route to be followed in the eastern section had even been determined. The locations were surveyed out by John Anderson-Thompson.[6] Siting crews covered the area – first from the air and then on the ground – to locate by scientific means the best sites for the main, auxiliary, and intermediate stations. These hardy men lived and worked under the most primitive conditions. They covered vast distances by airplanes, snowmobiles, and dog sleds, working in blinding snowstorms with temperatures so low that ordinary thermometers could not measure them. But they completed their part of the job on schedule and set the stage for the small army of men and machines that followed. The line consisted of 63 stations stretching from Alaska to Baffin Island, covering nearly 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi). The US agreed to pay for and construct the line, and to employ Canadian labor as much as possible.

A target date for completing the DEW Line and having it in operation was set for 31 July 1957. This provided only two short Arctic summers adding up to about six months in which to work under passable conditions. Much of the work would have to be completed in the long, dark, cold, Arctic winters.

Construction process

From a standing start in December 1954, many thousands of skilled workers were recruited, transported to the polar regions, housed, fed, and supplied with tools, machines, and materials to construct physical facilities – buildings, roads, tanks, towers, antennas, airfields, and hangars – in some of the most hostile and isolated environments in North America. The construction project employed about 25,000 people.

Military and civilian airlifts, huge sealifts during the short summers, snowcat trains, and barges distributed vast cargoes along the length of the Line to build the permanent settlements needed at each site. Much of the job of carrying mountains of supplies to the northern sites fell to military and naval units. More than 3,000 U.S. Army Transportation Corps soldiers were given special training to prepare them for the job of unloading ships in the Arctic. They went with the convoys of U.S. Navy ships and they raced time during the few weeks the ice was open to land supplies at dozens of spots on the Arctic Ocean shore during the summers of 1955, 1956, and 1957.

Scores of military and commercial pilots, flying everything from small bush planes to four-engined turboprops, were the backbone of the operation. USAF LC-130 aircraft, operated by the 139th Airlift Squadron, provided a significant amount of airlift to sites like Dye 3 that were out on ice caps such as the ones in northern Greenland. C-124 Globemaster and C-119 Flying Boxcar transport planes also supported the project. Together, these provided the only means of access to many of the stations during the wintertime. In all, 460,000 tons of materials were moved from the US and southern Canada to the Arctic by air, land, and sea.

As the stacks of materials at the station sites mounted, construction went ahead rapidly. Subcontractors with a flair for tackling difficult construction projects handled the bulk of this work under the direction of Western Electric engineers. Huge quantities of gravel were produced and moved. The construction work needed to build housing, airstrips, aircraft hangars, outdoor and covered antennas, and antenna towers was done by subcontractors. In all, over 7,000 bulldozer operators, carpenters, masons, plumbers, welders, electricians, and other tradesmen from the US and southern Canada worked on the project. Concrete was poured in the middle of Arctic winters, buildings were constructed, electrical service, heating, and fresh water were provided, huge steel antenna towers were erected, airstrips and hangars were built, putting it all together in darkness, blizzards, and subzero cold.

After the buildings came the installation of radar and communications equipment, then the thorough and time-consuming testing of each unit individually and of the system as an integrated whole. Finally all was ready, and on 15 April 1957 – just two years and eight months after the decision to build the Distant Early Warning Line was made – Western Electric turned over to the Air Force on schedule a complete, operating radar system across the top of North America, with its own communications network. Later, the system coverage was expanded even further: see Project Stretchout and Project Bluegrass.

The majority of Canadian DEW Line stations were the joint responsibility of the Royal Canadian Air Force (the Canadian Forces) and the U.S. Air Force.[5] The USAF component was the 64th Air Division, Air Defense Command. The 4601st Support Squadron, based in Paramus, New Jersey, was activated by ADC to provide logistical and contractual support for DEW Line operations. In 1958, the line became a cornerstone of the new NORAD organization of joint continental air defense.

USAF personnel were limited to the main stations for each sector and they performed annual inspections of auxiliary and intermediate stations as part of the contract administration. Most operations were performed by Canadian and US civilian personnel, and the operations were automated as much as was possible at the time. All of the installations flew both the Canadian and US flags until they were deactivated as DEW sites and sole jurisdiction was given to the Canadian Government as part of the North Warning System in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Radar system

The Point Lay, Alaska DEW line station has a typical suite of systems. The main AN/FPS-19 search radar is in the dome, flanked by two AN/FRC-45 lateral communications dishes (or AN/FRC-102, depending on the date). To the left are the much larger southbound AN/FRC-101 communications dishes. Not visible is the AN/FPS-23 "gap filler" doppler antenna.

The DEW Line was upgraded with fifteen new AN/FPS-117 passive electronically scanned array radar systems between 1985 and 1994, and the line was then renamed the North Warning System.

Operating characteristics of the AN/TPS-1D (Mod c) search radar

- Frequency range 1.22 to 1.35 GHz

- Peak power output 160 kilowatts

- Average power output 400 watts

- Pulse rate 400 pulses per second

- Pulse width 6.0 microsecond

- Range 1000 yards to 160 nautical miles

- Antenna radiation pattern

- Horizontal 2.8-degree

- Vertical 30 deg cosecant2 (elevation angle)

- Receiver noise figure 11.7 dB

- IF bandwidth and frequency 5.0 MHz and 60 MHz

- Required prime power 8.5 kW

- Weight of radar about 4800 pounds

- Total volume of radar electronics about 1000 cubic feet

Modifications to each operating radar station occurred during the construction phase of the DEW Line system. This was due to the extreme winds, frigid temperatures, and the ground conditions due to permafrost and ice.[9] There were two significant electronic modifications that were also crucial to the functioning of these radar stations in an arctic environment. One reduced the effects of vibration in correlation to temperature change, the other increased the pulse duration from two to six microseconds. It also began using a crystal oscillator for more stable readings and accurate accounts of movement within the air.

Operations

There were three types of stations: small unmanned "gap filler stations" that were checked by ground crews only every few months during the summer; intermediate stations with only a station chief, a cook, and a mechanic; and larger stations that had a variable number of employees and may have had libraries, forms of entertainment, and other accommodations. The stations used a number of long-range L band – emitting systems known as the AN/FPS-19. The "gaps" between the stations were watched by the directional AN/FPS-23 doppler radar systems, similar to those pioneered only a few years earlier on the Mid-Canada Line. The stations were interconnected by White Alice, a series of radio communications systems that used tropospheric scatter technology.

For stations at the western end of the line, buildings at the deactivated Pet-4 US Navy camp at Point Barrow were converted into workshops where prefabricated panels, fully insulated, were assembled to form modular building units 28 feet long, 16 feet wide, and 10 feet high. These modules were put on sleds and drawn to station sites hundreds of miles away by powerful tractors. Each main station had its own airstrip – as close to the buildings as safety regulations and the terrain permitted. Service buildings, garages, connecting roads, storage tanks, and perhaps an aircraft hangar completed the community. Drifting snow was a constant menace. Siting engineers and advance parties learned this the hard way when their tents disappeared beneath the snow in a few hours. The permanent "H" shaped buildings at the main stations were always pointed into the prevailing winds and their bridges built high off the ground.

The arctic region was frequently transited by commercial aircraft on polar routes, either flying between Europe and western North America, or between Europe and Asia using Alaska as a stopover. These flights would penetrate the DEW Line. To differentiate these commercial flights from Soviet bombers, the flight crews had to transmit their flight plan to an Air Movement Identification System (AMIS) center at either Goose Bay, Edmonton, or Anchorage. These stations then passed the information on to the DEW Line.[11] If an unknown flight was detected, the DEW Line station would contact AMIS to see if a flight plan might have been missed; if not, NORAD was notified. Military flights, including B-52 bombers, frequently operated in the polar regions and used IFF systems to authenticate the flight.

The early warning provided was useless against ICBMs and submarine-launched attacks. These were countered and tempered by the MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) philosophy. However, the scenario of a coordinated airborne invasion coupled with a limited nuclear strike was the real threat that this line protected against. It did so by providing Distant Early Warning of an inbound aerial invasion force, which would have to appear at the far north hours ahead of any warhead launches in order to be coordinated well enough to prevent MAD. A number of intermediate stations were decommissioned, since their effectiveness was judged to be less than desired and required. The manned stations were retained to monitor potential Soviet air activities and to allow Canada to assert sovereignty in the Arctic. International law requires a country that claims territory to actively occupy and defend such territory.

Because the advent of ICBMs created another attack scenario that the DEW Line could not defend against, in 1958 the U.S. Federal Government authorized construction of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS), at a reported cost of $28 billion.

In 1985, it was decided that the more capable of the DEW Line stations were to be upgraded with the GE AN/FPS-117 radar systems and merged with newly built stations into the North Warning System. Their automation was increased and a number of additional stations were closed. This upgrading was completed in 1990, and with the end of the Cold War and dissolution of the Soviet Union, the US withdrew all of its personnel and relinquished full operation of the Canadian stations to Canada. Costs for the Canadian sector were still subsidized by the US. However, the American flags were lowered at the Canadian stations and only the Canadian flag remained. The US retained responsibility and all operational costs for North Warning System stations located in Alaska and Greenland.

Canadian perception

From the beginning of the development of the DEW Line idea, Canadian concerns over political perception grew enormously. Noted Canadian Arctic historian P. Whitney Lackenbauer argues that the Canadian Government saw little intrinsic value in the Arctic, but due to fear of Americanization and American penetration into the Canadian Arctic, brought significant changes and a more militaristic role to the north.[12] This shift into a more military role began with a transition of authority, shifting responsibility of Arctic defense in Canada from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to the Canadian Forces. This "active defense" had three key elements: minimizing the extent of the American presence in the Canadian Arctic, Canadian government input into the management of the DEW Line, and full Canadian participation in Arctic defense.

Funding problems for the DEW Line also played a role in perception of the project. American investment in building and operating the DEW Line system declined as the ICBM threat refocused priorities, but Canada did not fill the void with commensurate additional funding. In 1968 a Canadian Department of National Defence Paper (27 November 1968) stated no further funding for research on the DEW Line or air space defense would be allocated due in part to lack of commercial activity[14] The Canadian Government also limited U.S. air activity, base activity, soldier numbers, and contractor numbers; and the overall operation would be considered and called in all formalities a "joint operation".

Cultural impact

The cultural impact of the DEW Line System is immense and significant to the heritage of Canada, as well as Alaska. In Canada, the DEW line increased connections between the populous south and the remote High Arctic, helping to bring Inuit more thoroughly into the Canadian polity. [16] The construction and operating of the DEW Line provided some economic development for the Arctic region. This provided momentum for further development through research, new communications, and new studies of the area. Although the construction of the DEW line itself was placed in American hands, much of the later development was under direct Canadian direction.[17] Resource protection of historical DEW Line sites is currently under discussion in Canada and Alaska. The discussion stems from the deactivation aspect of the sites and arguments over what to do with leftover equipment and leftover intact sites. Many Canadian historians encourage the preservation of DEW Line sites through heritage designations.

The DEW Line is a setting for the 1957 film The Deadly Mantis. The film begins with a short documentary on the three RADAR lines, focusing on the DEW Line's construction.

Deactivation and clean-up

A controversy also developed between the United States and Canada over the cleanup of deactivated Canadian DEW Line sites. The cleanup is now underway, site by site.[18] In assessing the cleanup, new research suggests that off-road vehicles damaged vegetation and organic matter, resulting in the melting of the permafrost, a key component to the hydrological systems of the areas.[19] The DEW Line has also been linked to depleted fish stocks and carelessness in agitating local animals such as the caribou, as well as non-seasonal hunting. These aspects are claimed to have had a devastating impact on the local native subsistence economies and environment.

Atlantic and Pacific Barrier

The DEW line was supplemented by two "barrier" forces in the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans which were operated by the United States Navy from 1956 to 1965. These barrier forces consisted of surface picket stations, dubbed "Texas Towers", a surface naval force of twelve radar picket destroyer escorts and sixteen Guardian-class radar picket ships, and an air wing of Lockheed WV-2 Warning Star aircraft that patrolled the picket lines at 1,000–2,000 m (3,000–6,000 ft) altitude in 12- to 14-hour missions. Their objective was to extend early warning coverage against surprise Soviet bomber and missile attack as an extension of the DEW Line.

The Atlantic Barrier (BarLant) consisted of two rotating squadrons, one based at Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland, to fly orbits to the Azores and back; and the other at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland. BarLant began operations on 1 July 1956, and flew continuous coverage until early 1965, when the barrier was shifted to cover the approaches between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom (GIUK barrier). Aircraft from Argentia were staged through NAS Keflavik, Iceland, to extend coverage times.

The Pacific Barrier (BarPac) began operations with one squadron operating from NAS Barbers Point, Hawaii, and a forward refueling base at Naval Station Midway, on 1 July 1958. Planes flew from Midway Island to Adak Island (in the Aleutian Island chain) and back, non-stop. Its orbits overlapped the radar picket stations of the ships of Escort Squadron Seven (CORTRON SEVEN), from roughly Kodiak Island to Midway and Escort Squadron Five (CORTRON FIVE), from Pearl Harbor to northern Pacific waters. Normally 4 or 5 WV-2s were required at any single time to provide coverage over the entire line. This coverage was later augmented, and modified/replaced by Project Stretchout and Project Bluegrass.

The Guardian-class radar picket ships were based in Rhode Island and San Francisco, and covered picket stations 400–500 miles off each coast.

Barrier Force operations were discontinued by September 1965 and their EC-121K (WV-2 before 1962) aircraft placed in storage.