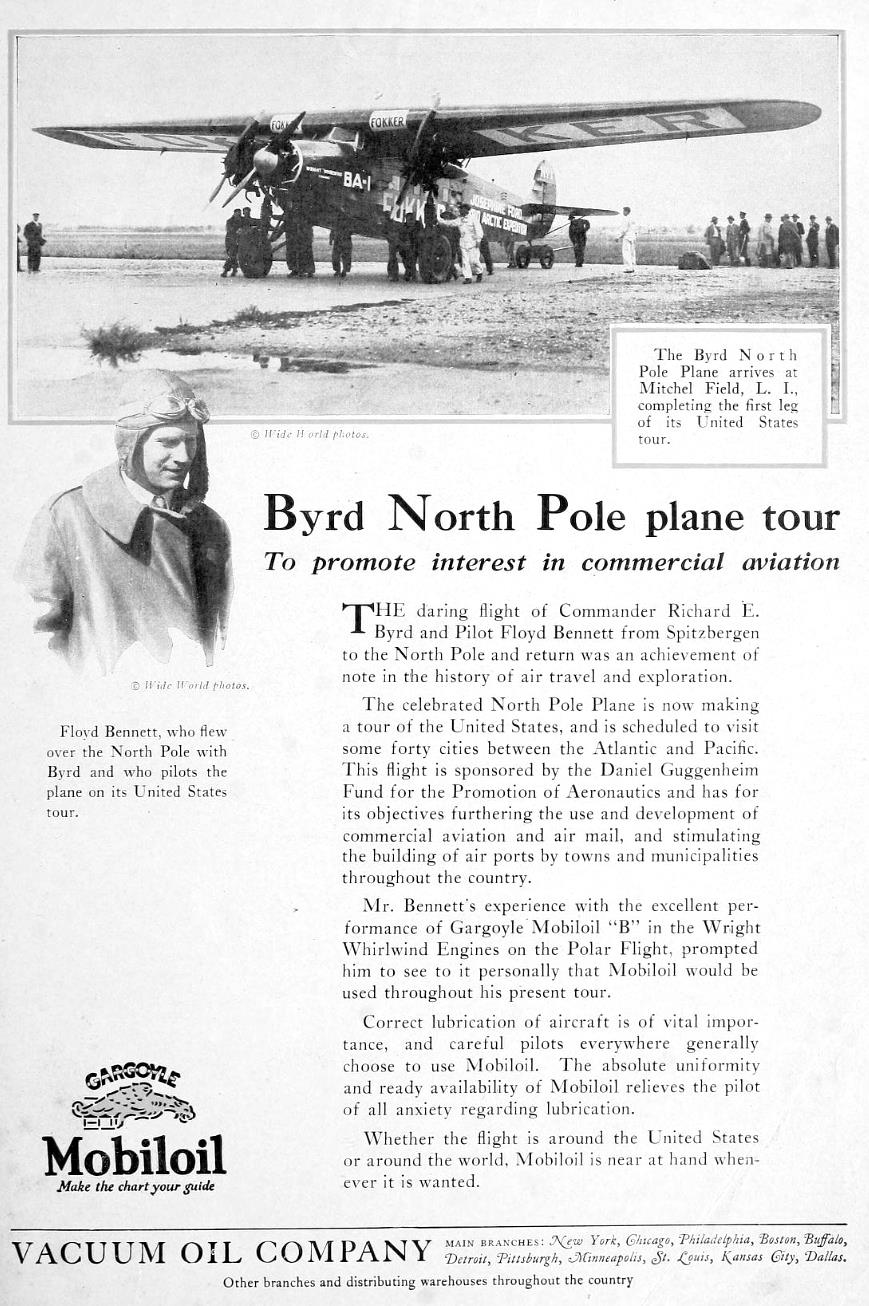

Byrd Flies North

Aero Digest - May, 1926 - Page 257

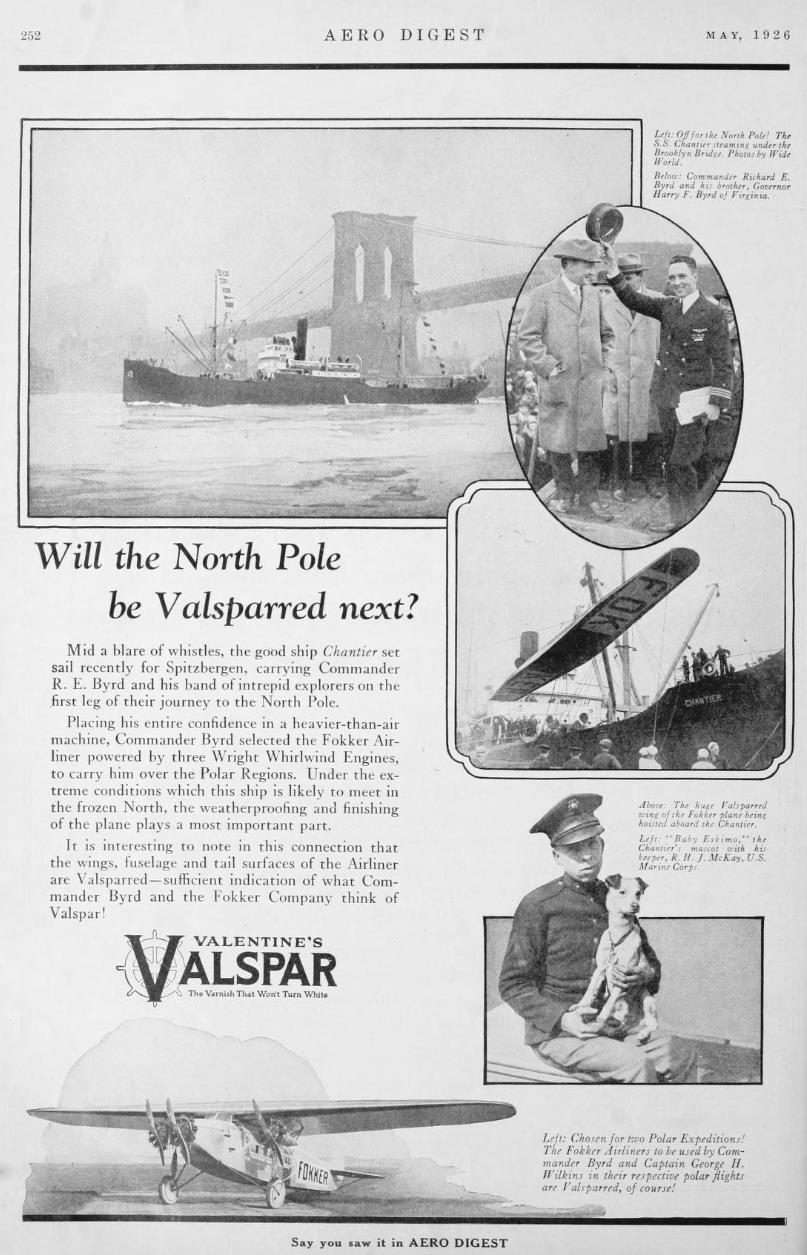

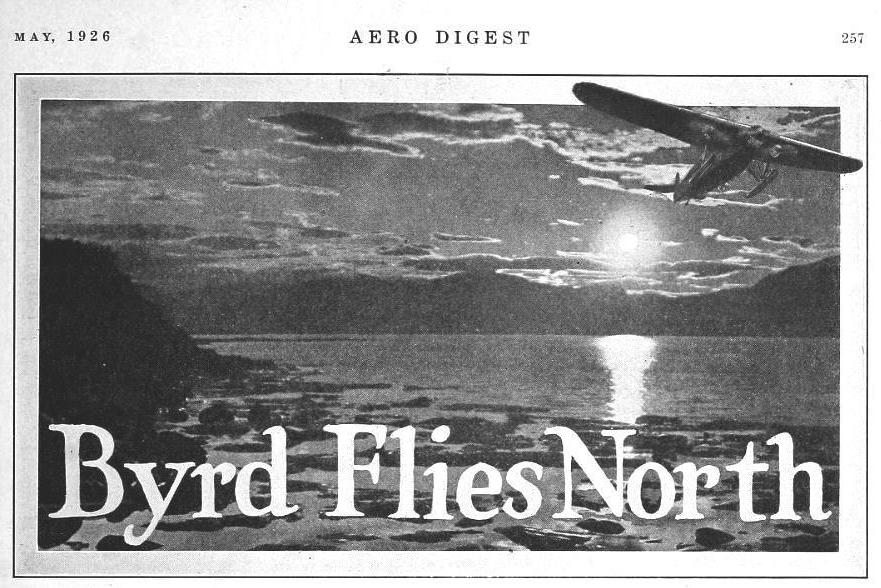

Beneath a fluttering banner portraying the American eagle perched on top of the world, Lieut. Commander Richard E. Byrd and the forty-seven volunteers accompanying him started northward.

With the advance of spring, Commander Byrd hastened his departure in order to make his flights before the mists and fogs make more difficult the accomplishment of his purpose.

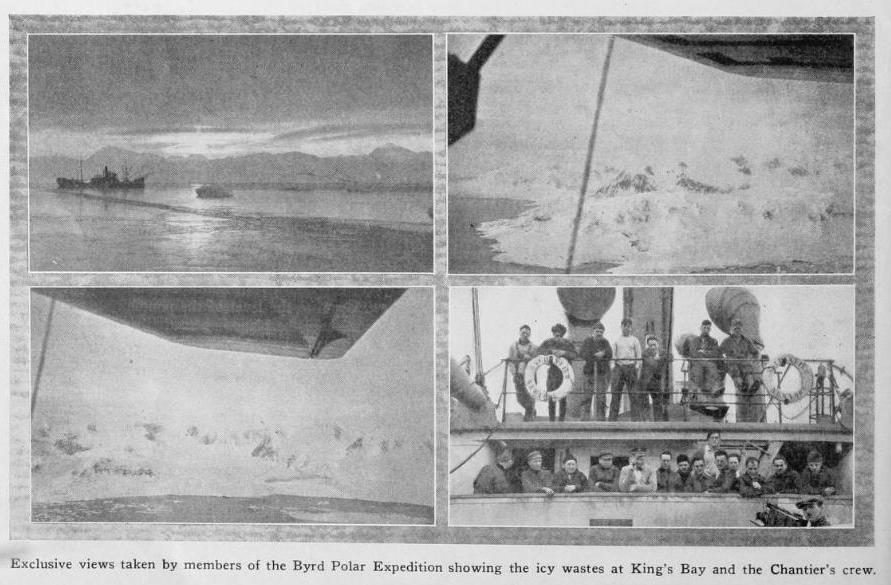

Brave men, these! Facing unknown perils to further the cause of science. Daring the uncertainties of arctic flying to prove the value of aeronautics in another field—as a means of unlocking the untold secrets of the frozen north. Flying confidently under their symbol of success, no ship ever carried a more enthusiastic company than the Chantier. The spirit of adventure and patriotism filled leader as well as mess-boy.

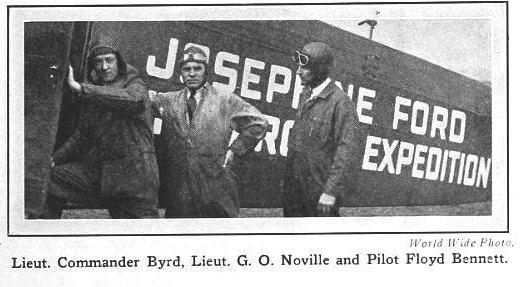

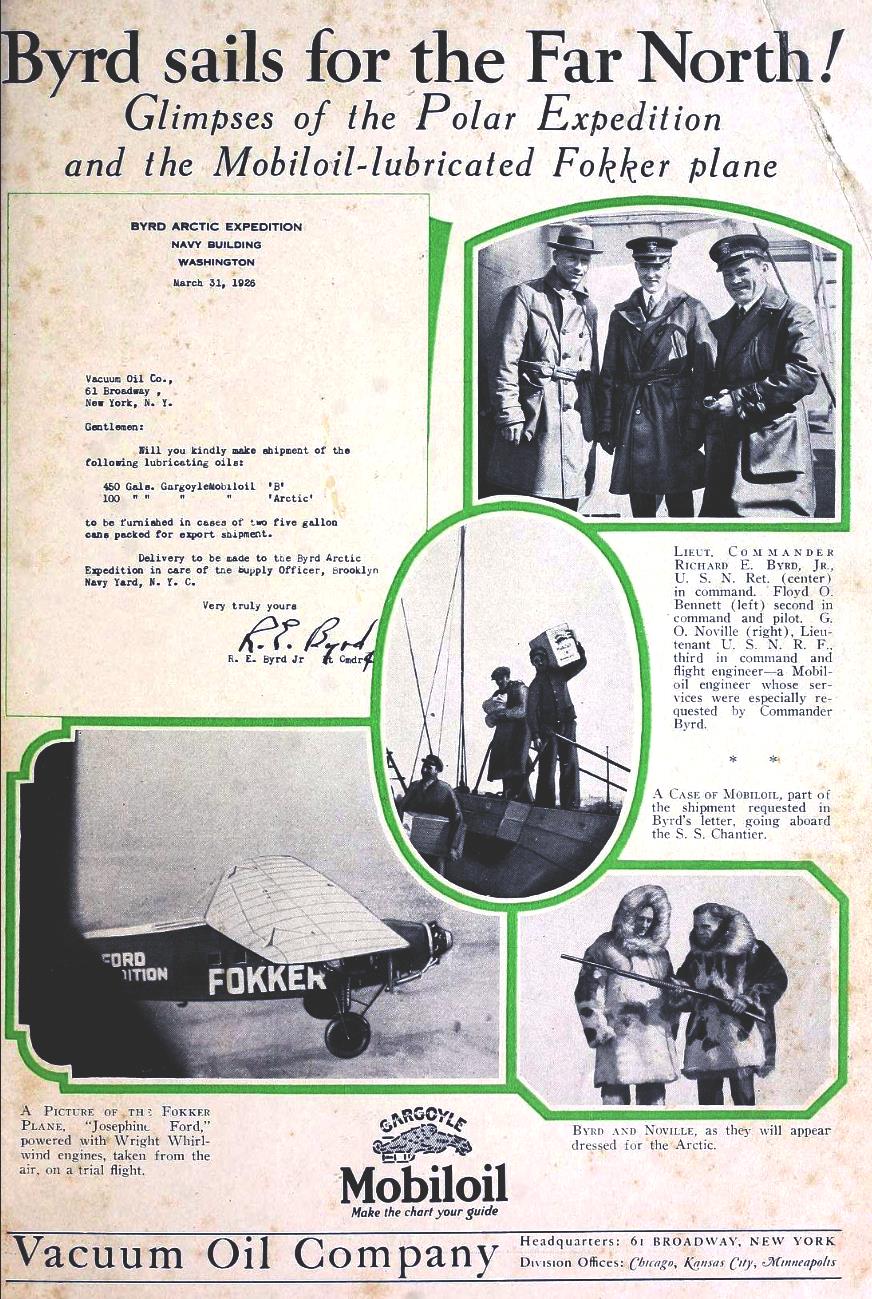

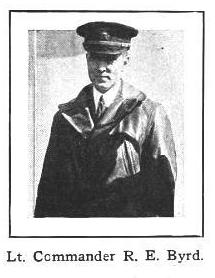

With Commander Byrd, who is a profound student and inventor of many air navigation instruments, are the following experts: Floyd Bennett, pilot-mechanic; Lieut. G. 0. Noville, of the Vacuum Oil Company, flight and fuel engineer; reserve pilot, R. C. Ortel; mechanic, L. M. Peterson and T. H. Kincaid, engine expert from the Wright Aeronautical Corporation.

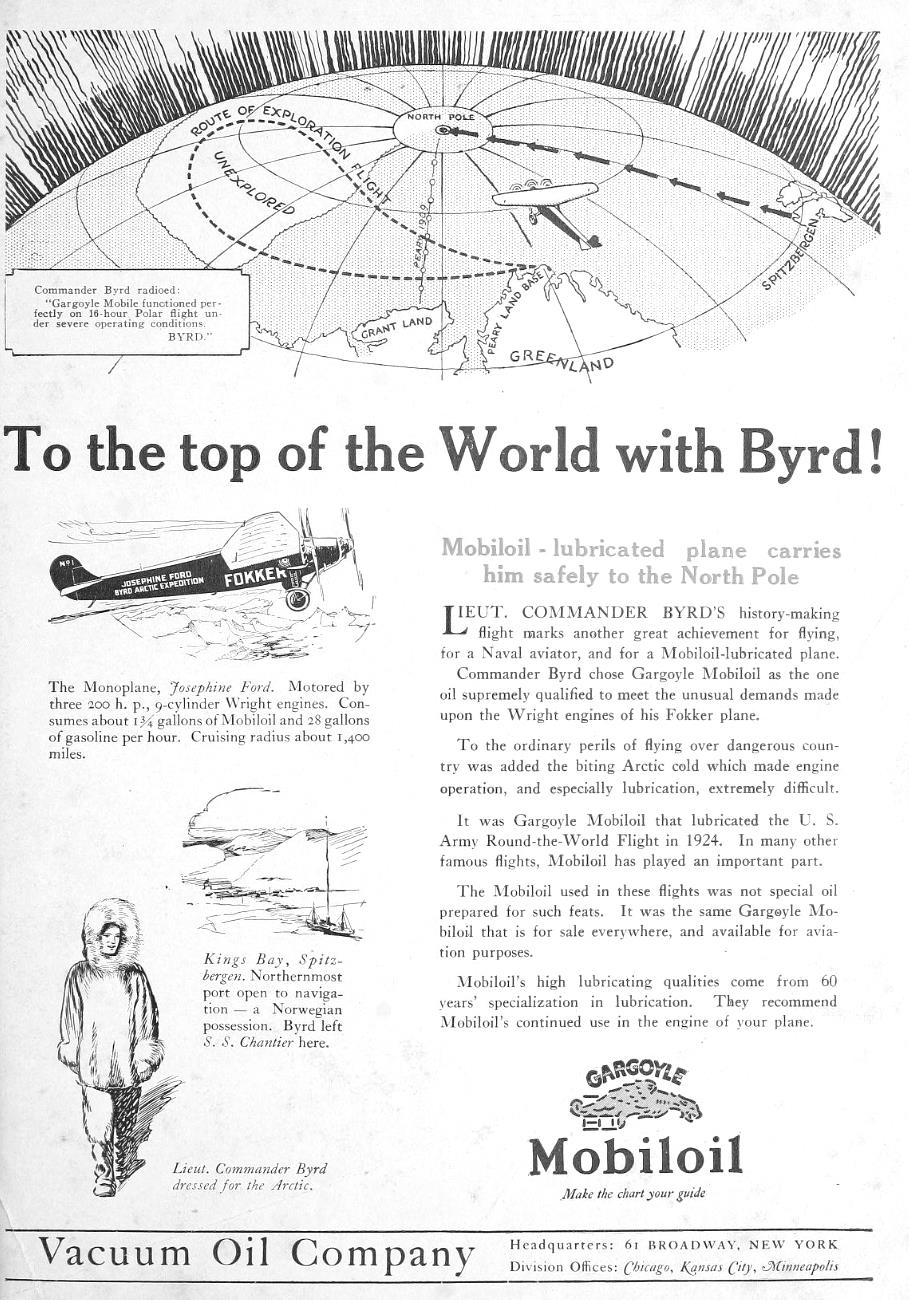

The Chantier is bound first for Tromso, Norway, which was Andree's base in his attempt to reach the Pole by balloon in 1897. There an ice pilot will join them to take the ship through the icebergs to King's Bay, Spitzbergen. The first flight, to carry food and supplies, will start from Spitzbergen to Peary Land, 400 miles distant, the northernmost known land in the world. They will then fly back to Spitzbergen and take another load to the Peary Land base, after which the attempt will be made to fly the 450 miles to the North Pole.

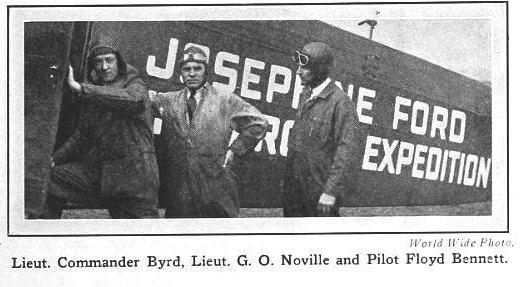

Their objective is not primarily to reach the Pole but to make a survey of the unexplored area surrounding it. The flying equipment of this expedition consists of the Fokker type F VIII. equipped with three Wright J-4 200 h.p. air-cooled engines, which will make the main flight, and a Curtiss Oriole, which is to be used as an auxiliary.

The Fokker wing measures 63 feet 3 inches from tip to tip, is 49 feet 2 inches long and 12 feet 9 inches high. The fuel capacity is 420 gallons of gasoline, carried in two 100-gallon tanks located in each wing and two specially built 110-gallon tanks located in the fuselage of the machine. Tests proved a gasoline consumption of 28 gallons per hour and a cruising speed of 100 miles. Complete radio equipment is installed, consisting of a receiver and a 50-watt transmitter. The call letters assigned to it are KEGK. Skiis will replace the landing wheels.

Our Flight over the North Pole

SEPTEMBER, 1926 - AERO DIGEST Page 175

Bennett and Byrd—first to fly over the North Pole.

By Floyd Bennett

This is the First Exclusive Story by the Pilot of the Josephine Ford on the North Pole Flight

OUR expedition left New York April 5th, with a crew of 52 men aboard the S. S. Chantier, the 3,500-ton steamer supplied to us by the U. S. Shipping Board. We carried two airplanes, a small Curtiss Oriole, to be used for finding a suitable landing field for our big three-motored Fokker monoplane, the Josephine Ford, which was to carry Commander Byrd and me from Spitzbergen to the North Pole. Our 1,500 tons of supplies and equipment was sufficient for a cruise of 10,000 miles.

On the morning of April twenty-ninth we sighted Spitzbergen and at 4:30 that afternoon entered King's Bay where we were met by Lieutenant Ulling of the Norwegian gunboat Heimdal. He piloted the Chantier to a berth alongside his ship. We had hoped to find the bay solidly frozen over so that we could tie up the Chantier alongside the ice barrier and land the Josephine Ford with our supplies and make our attempt from the ice as Amundsen had done last year. But the few small floes were barely large enough to support the weight of a man. The season was the most advanced in years. We had to devise other plans immediately. To have waited for a place alongside the dock would have delayed us too long, as the Heimdal would be coaling there for the next four or five days.

A party, composed of Commander Byrd, "Doc" Kinkade, Doctor O'Brien, Peterson, Touchette and I went ashore in search of a landing field and base. A large space between the village of King's Bay and the hangar built for the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile airship Norge, about a mile wide and a mile and one-half long, would give us a runway for the take off about 600 yards long; it was down grade 5 per cent and as good a landing place as we could hope for. One drawback was that it was a one-way field, and we could not take advantage of the wind in getting off and landing. But there was no other place in the vicinity. Our next problem was to get our equipment ashore. The snow was coming down fast and the bay was freezing over. It was miserable weather. We worked all night in cold slush and sleet that at times obscured everything more than fifteen feet distant. By morning however, the first load, the Oriole, had been taken ashore through gathering ice floes, and greeted the inhabitants when they awoke and came to watch us with curiosity which often developed amusement for us all.

We had chopped a runway through the edge of the ice, cutting it down to the level of the pontoon we constructed so we could haul the planes up to the beach, and on these landed the small plane. The work had nearly exhausted the men, so we returned to the ship to sleep.

On the afternoon of the 30th we hoisted the fuselage of the Josephine Ford out of the hold and lashed it to a raft alongside the ship. A strong wind was blowing and the bay was filled with drifting ice, so we did not then attempt to place the large wing on the fuselage. We were compelled to keep men on the raft to push away floating ice cakes which would have broken the raft. The following morning, May 1st, was perfectly calm, but the bay was packed with drift ice. Conditions were perfect for hoisting out the big wing and placing and securing it on the fuselage. In about an hour we reached the beach.

The first big job of getting the plane on shore was done. Our two wing motors, gas and other supplies remained to be ferried over, but our success in surmounting obstacles in getting the plane ashore made us regard this as a small job. Two more trips with our ferry and we were through.

Our base camp on the shore was then established. Our plane motors were installed and we had the plane ready for the motor test on May 3rd. We were working under difficult conditions. The temperature was 7 degrees (F) below zero and several of the men had frostbitten hands and feet. We had worked almost continuously for three days and greatly needed sleep before attempting our test flight. It was difficult for us to sleep with the constant daylight—one could work until nearly exhausted and still not feel the need of sleep. It is an odd sensation to wake at midnight and find the sun shining as at noon.

On May 4th we were ready for the first engine test. The difficulty of starting our three Wright "Whirlwind-air-cooled engines in the extreme cold had been anticipated before leaving New York. Therefore, for each motor we made a hood or cover of fireproof canvas which fitted snugly around the motor with a funnel-like extension below the motor. Three gasoline stoves with vertical blow torch burners were placed so the heat would be carried through the canvas ducts to the hoods. The heated air thus circulating around the engines warmed them up in a few minutes. The oil tanks were filled with warm oil. After these preparations the motors started as easily as in a temperate climate,—a tribute to our Flight Engineer, Lt. Noville.

We were next ready to try the skis. To my knowledge no plane of this size has ever been started on skis, especially with a useful load of 6,000 pounds. I had never flown any plane with skis, and had little knowledge as to how the plane would act. A test flight of at least two hours was decided on before the final start, to give us a chance to see how our motors would function under these severe conditions.

Finally all was ready. One motor was opened. Nothing happened! Two motors were opened and still nothing happened. With the third motor wide open our plane did not move an inch! After considerable effort we finally got the plane moving, taxied away up the hill, and turned around for the trial take-off. Again all motors would not start the plane moving and the crew gathered around to give a lift for a start. Touchette, who was standing near, found a break in the main fitting which secures the landing gear to the fuselage. The ship was strong enough for use with wheels, for which it was designed, but when equipped with skis and either of the wing motors used separately there is a terrific strain on the landing gear, because the skis do not turn on the snow as easily as wheels on the ground. It requires a larger space to turn a plane when equipped with skis. We found that a crew of men could not lift the tail of the plane and turn it, as is usual in turning a ship with wheels. It was by attempting this that we broke the first set of skis and landing fittings. We had come prepared for trouble and had an extra landing gear and two extra sets of skis. But it means time and labor to change them on a plane weighing 4,000 pounds and in four feet of light snow. It was necessary to dig down

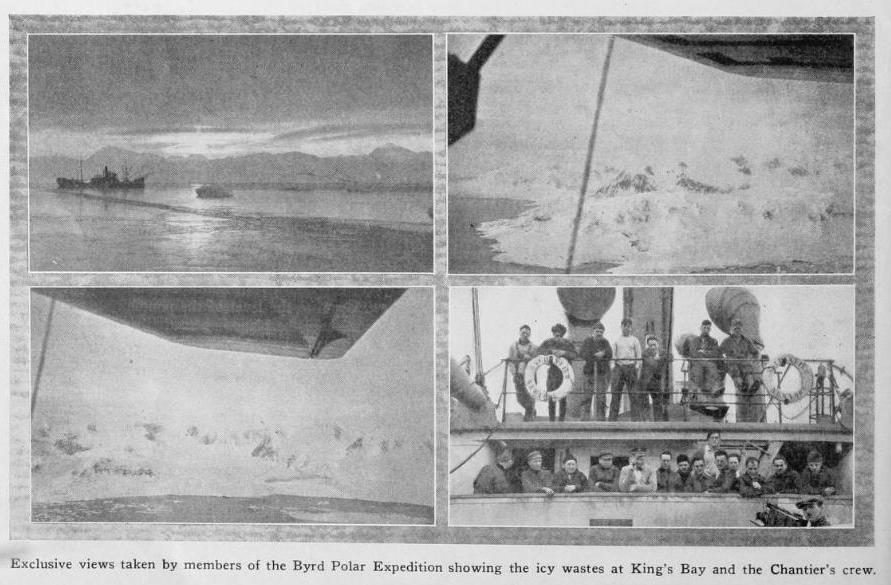

Exclusive views taken by members of the Byrd Polar Expedition showing the icy wastes at King's Bay and the Chantier's crew.

---

SEPTEMBER, 1926 AERO DIGEST - Page 177

through the snow in four places and build a foundation of gasoline drums upon which we could place jacks and raise the plane clear of the landing gear. This was a delicate operation as an increase of wind might have forced the plane off the jacks and the expedition would have reached its end. No plane, no flight.

After fifteen hours of hard work we were again ready to attempt the test flight. Lieutenant Parker and I were at the controls of the big plane and Flight Engineer Noville and Mechanician Peterson in the cabin. It was necessary to make a slight turn to the right as we got under way as we had cleared only a narrow runway and there was a snow bank on the left. The plane did not move until all three motors were opened. Then the left ski stuck slightly and the plane headed to the left instead of to the right, which caused the left ski to catch and break in a snow bank just as we had nearly cleared it. The plane whirled around and, as the ski broke, plunged her nose into the snow. This experience increased our respect for the snow. We were learning.

One ski was ruined. one landing gear strut broken, and other members of the landing gear were badly bent. The metal propeller of the center motor was out of line and had to be replaced. We were getting quite experienced in jacking up the plane in the snow, but this meant another day's work and delay which was serious. Every day lessened our chances should we have to walk back over the polar sea. The sooner we could get away the less fog we would encounter upon our flight, and naturally we hoped to be the first to reach the pole by air.

On May 5th we were ready for another attempt to get off on our test flight. Everything was set, the motors turning up and it seemed as though every possible precaution was taken. The Norge was due the next day and as we were quite close to the entrance of their hangar it would be necessary to move our plane before they could land. Lieutenant Parker and I were in the pilot's cockpit and Lieutenant Noville and Peterson in the cabin. With motors wide open we gained speed as we glided down grade. It looked as though we would make it. Off at last! What a glorious sensation to be in the air after all that work. I wished then that the ship was loaded and headed for the North Pole.

At the end of an hour everything was fine and the motors going great. The temperature and pressures remained constant and everything looked favorable. Suddenly after about an hour and thirty minutes in the air there was an alarming vibration throughout the plane accompanied by a dull hum. The motors were throttled preparatory to landing when it occurred to me what the trouble might he. The plane was equipped with radio and the small electric generator was mounted on the outside of the fuselage just off the cockpit. I looked out just in time to see the generator torn from its mounting. A portion of it went overboard, the balance hanging on about four feet of wire, Noville and Petersen had seen the generator and by opening a window in the cabin, reached down and pulled it in. We continued our flight for a period of two hours and thirty minutes with no further trouble.

Our first landing on skis was made, which we found not at all difficult, and the plane turned around by hand and headed down grade, where it would start on its history-making flight.

Final examination of plane and motor showed me we had a leaking oil tank on the starboard motor. This we removed and repaired, and a new radio generator was installed. All that remained for us to do was to load the plane with the fuel and equipment and give the motors a final looking over. Our equipment consisted of about three hundred pounds of food, mostly pemmican; two twelve-pound portable rubber boats with paddles; a tent built especially for us; two pairs of snow shoes; a sledge built for us in Spitzbergen; a thirty-caliber Remington rifle and a twelve-gauge shot gun; 300 rounds of rifle ammunition and 200 rounds of shotgun ammunition; an extra parka; two pairs of winter mukluks and two pairs for summer; an extra pair of reindeer trousers; and a total of 615 gallons of gasoline and 40 gallons of oil (sufficient for a flight of at least twenty hours), 410 gallons of this gasoline was in our tanks and 200 in 5-gallon cans to be emptied through a chamois into the main tanks during flight.

The seventh of May was spent in getting the gear stored in the plane. While this was being done, Peterson and Kincaid were carefully inspecting the motors. On May 8th, about 12:30 G.M.T. we were ready for the great adventure. The motors were warmed up and "good byes" were said. I would have preferred to omit the "good byes" as I was not so sure we would get off. The plane was loaded to capacity; our total useful load being 6,000 pounds, 500 pounds more than we had taken off with On our test flight at Mitchel Field, New York.

Everything was set to go. Motors opened wide, the plane started slowly down the long runway. We moved along 100 yards before our motors were full out but still I thought we could get off. So we continued down the long runway, our speed gradually increasing until we reached the end of the runway where we had packed the snow. I knew that if we could not clear the snow here there would be no use continuing further, for as soon as we came in contact with the soft snow we would lose speed. At the end of the runway I made a final attempt to get the heavily-laden plane off the snow. It was unsuccessful as we had only about thirty-five miles air speed and it required around forty-five miles to ride with this load. I throttled the motors so as to stop before we reached the open waters of King's Bay, one hundred yards away; when the motors were throttled the plane stopped almost immediately.

(Continued on page 261)

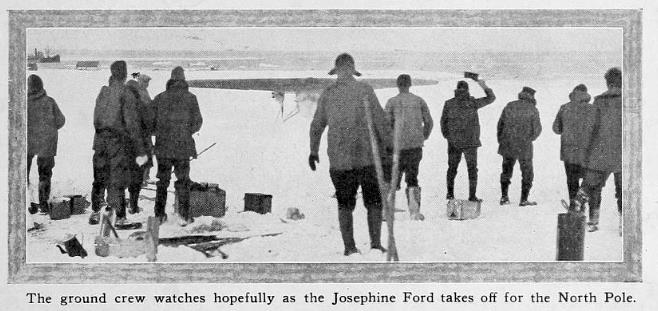

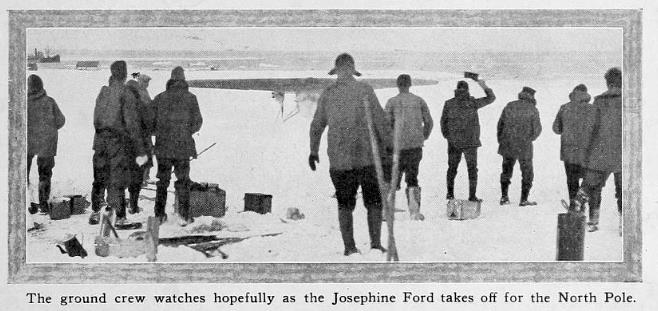

The ground crew watches hopefully as the Josephine Ford takes off for the North Pole.

--------

SEPTEMBER, 1926 AERO DIGEST page 261

OUR FLIGHT OVER THE NORTH POLE

(Continued front page 177)

We had failed in our first attempt. After all our work and worry we had failed to get off. To say that I was disappointed is putting it light. Then I thought of the crew who had worked almost continuously for the past forty-eight hours. They must have sleep and rest before any more work could be done. Every hour was vital to us as the weather was now perfect for our start. Buried as it was in the soft snow it seemed impossible to move the plane with its extremely heavy load without wrecking the landing gear. It was necessary to remove most of the 6,000 pounds of weight and carry it back to the top of the grade for another trial. The crew was tired out and needed sleep and it looked as though it would be some time before we could make another trial. If we could get the plane back to its starting place immediately we could make another attempt at once. Therefore we took out about 1,000 pounds of the load and within half an hour we had the big Josephine Ford back to the top of the hill for another start. With the plane back in this position the spirit of the crew rose. They felt there was still a chance. We decided to take out everything that we could possibly spare without greatly decreasing our cruising radius. By taking out various articles we reduced the weight about 450 pounds.

The runway was again smoothed out and the first hundred feet sprinkled with water to form ice which would better support the weight of the plane. The tail of the plane was secured so that the plane would not move until all three motors were developing full power. A line was passed around the tail skid and fixed to the ground, to be cut when our engines reached their full power. The gas and supplies were restored to the plane and all was in readiness.

The question arose as to whether we should start immediately or get some rest before going on the flight. Commander Byrd and I thought that we should go immediately but Captain Brennan of the Chantier insisted that we should get some rest first. We agreed to go to the ship and sleep for four hours. As we started down the runway towards the Chantier the Commander said, "Bennett, we ought to go while the weather is good." I answered. "Then let's go now."

We turned and walked back to the plane and gave instructions to have the motors warmed up and made ready. As this would take about two hours. I thought I might get a little sleep while this was being done, so put on my flying suit of reindeer and laid down on the snow to rest. But there was too much on my mind for sleep. I rested for about an hour.

At 12:50 A.M. (G.M.T.) on May 9th we were again in the plane and ready for another start, twelve hours after our first attempt. We had no "good byes" or handshaking this time. We took our places in the plane and when all motors were full out the signal was given to cut the line holding the tail skid. The plane glided smoothly down the long runway, rapidly increasing its speed. It was apparent immediately that this time we would get off. When a little more than half way down the runway we cleared the snow and were actually in the air. What a glorious feeling! After four months of preparation, with its many disappointments and uncertainties we were actually started on our flight to the pole.

It was a beautiful morning with the sun comparatively low on the horizon. Our first sixty miles took us along the coast of Spitzbergen and over open water. After this our course was directly north out into the great unknown.

We expected to find open water for the first hundred miles off the coast of Spitzbergen but the polar ice pack extended nearly to Danes Island. The edge of the pack was made of large fields of floating ice extending back a few miles before the solid pack was reached. We expected to find a belt of slush ice along the edge of the pack. We were not disappointed in not finding this slush ice for in case of motor failure we would have a better chance to land on the large fields of floating ice than in the small broken slush ice.

I thought we would find the polar sea a mass of broken ice with no chance to land without wrecking our ship. I was surprised at the condition of the ice; it did not appear nearly as rough as I had expected. Running in every direction there were great pressure ridges, from ten to twenty feet high, formed by cakes of ice of all sizes. It was a great network of pressure ridges, but between some of these ridges were fields of comparatively smooth ice. All of this great mass of ice was covered with snow and in many of the fields between the pressure ridges could plainly be seen large blocks of ice projecting out of the snow. Some of the fields which I observed closely seemed smooth and I believe that a plane could land with some chance of rising again. Of course there would be great risk.

I noted the various sizes and shapes of the sections between the pressure ridges. We saw three open leads of water resembling long winding rivers extending through the ice. Two of these were very narrow, perhaps thirty or forty feet in width. The third was somewhat larger, large enough, I believe, to land a large seaplane in. There seemed to be no great change in the condition of the ice throughout the entire flight. There was an occasional lead that had just recently frozen over, presenting a blue line across the glaring white surface.

Everything went along smoothly for the first six hours, Commander Byrd continually checking our course with his sun compass, taking the drift of the plane, using his sextant to determine our position and taking photographs, both still and motion pictures. He relieved me at the wheel about twenty minutes out of every hour so that I might check up the gas consumption and pour more gas into the tanks from the 40 five-gallon cans. We did not have much time to let our thoughts wander and perhaps it was just as well.

After about seven and one-half hours Commander Byrd reported an oil leak in the starboard motor. From the cabin he had a good view of the wing motors and could see the oil leaking out and covering the cowling and tail section. He came forward and took the controls and I went back into the cabin to see if I could determine the seriousness of the leak. It looked bad and I did not know how long the oil would last. It is not possible to get out to the motor. The oil tank was completely cowled in and covered with asbestos and over this a covering of canvas. Therefore there was no way to determine the position of the leak. If it should be at the bottom of the tank all of our oil would drain out in a short time and our motor would be useless. T returned to my seat and Commander Byrd asked, "Is it a bad leak?" I wrote on a pad "It is a bad leak and we may lose the motor at any time."

Then we throttled the leaking motor to determine if we could continue with the two remaining motors should we lose this one, and we were able to maintain our altitude of 2,000 feet with the two motors. I indicated to Commander Byrd that we might land and fix the motor. We decided however to continue the flight to the pole and if necessary to return on two motors.

For the next hour and thirty-five minutes Commander Byrd was busy with his sun compass, sextant, drift indicators and cameras. Suddenly he came forward and-shook hands with me. We had reached the pole!

We circled at the pole and then started on our return. The sun was now almost directly in front of us to the left, that is, it passed across the windshield from left to right, and I was able to use it as a check in holding my course. After about six hours on our return course I sighted what I thought to be land but as I was not sure I did not call the Commander's attention to it. After another fifteen minutes I was sure it was land and it certainly looked good. It was apparent we were making better speed on our return than going out.

We were about a hundred miles from land when it was first sighted as it took us about an hour to reach the coast of Spitzbergen. The remarkable thing was that the oil pressure was still up on the starboard motor, although half of the oil had leaked away. (Later examination on our return showed the leak was due to a rivet coming loose half way down the tank.) We neared the coast of Spitzbergen within one mile of the point toward which Commander Byrd had set the course—a tribute to his skill as a navigator.

Now we had only one hour more to reach King's Bay. I was glad of that as I had been awfully sleepy for the past two hours. I spiraled down for a landing and came over the field to land. As there were too many people where I wanted to land, I had to make another circle of the field. This time there was a place clear and we settled down safely on the snow and taxied up to the place we left sixteen hours before. Our mission was accomplished, and at last I could get some sleep!

-----